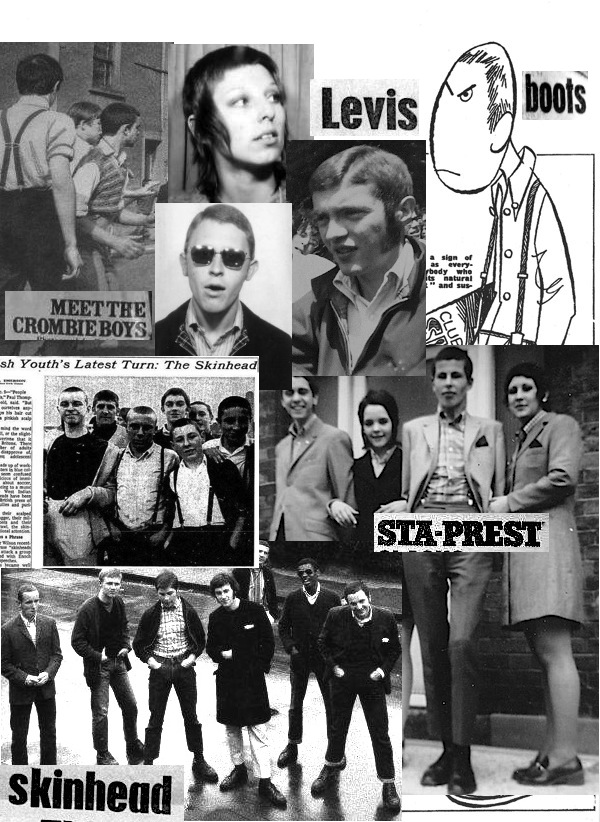

2019 will see the 50th anniversary of the year when the word ‘Skinhead’ hit the UK media. In time for that semicentennial, ‘The Firm’ – a group of people who were there when it all kicked off – converse with each other, and respond to questions. What was it really like in 1969?

Bookseeker Agency frontman Paul Thompson was invited to be the editor for the book, although it really was a collective effort. BBC Radio6 DJ Don Letts has promised a foreword in due course – you may have seen Paul on Don’s 2016 documentary The Story of Skinhead on BBC4, as he was there back in the day too!

Walk Proud tackles such issues as

Did Skinheads evolve from the Mods?

What was the link to the American ‘Ivy League’ style, and where did Skins get those button-down shirts and wing-tip brogues?

Was it all boots and braces and football?

Were there run-ins with Greasers, the Old Bill, and South Asians?

Drugs or booze?

What did Skinhead girls really wear?

Yell – the invention of the modern fanzine, or a mistake that never got off the ground?

Race and politics.

Was Skinhead essentially a London thing?

Slade or Desmond Dekker – what was the true ‘sound’ of Skinhead?

Skinheads and the media – “Do they mean us?”

They don’t always agree with each other, but their conversations bring out details which might otherwise have been lost to social history. That’s one of the main reasons why the book has been put together. The media, both reportage and drama, have been getting things wrong almost since day one, from Softly Softly Task Force to Inspector George Gently, and later copycat movements have turned the whole thing into a para-political travesty. So this book is a vital piece of that social history.

The book is now going out to publishers. But if you’re a non-fiction publisher and you’re reading this and you think you can market it, don’t wait for us to get in touch with you!

__________

The artwork and images in this article are not necessarily from the book.

Paul writes:

Paul writes: It has often been said before when it comes to history – “Where are the women?” We have the impression, due to ‘taught’ history seeming to be a procession of great men, great battles, great events, that half the world’s population is invisible, and that this invisibility is somehow uniform throughout history. Sarah presents Renaissance women to us in her novels – in convents, as courtesans, at court – living unexpectedly rich and varied lives, even though they may be distanced from direct involvement in the ‘great events’. Lucrezia Borgia is almost invisible, except for the gossip put around by enemies of the Borgias. Pinturicchio’s depiction of St Catherine of Alexandria may be the closest we have to a portrait of her, but as a dynastic asset she was arguably as important as her father Rodrigo and her brother Cesare. Although she was only thirty-nine when she died of natural causes, she outlived them both.

It has often been said before when it comes to history – “Where are the women?” We have the impression, due to ‘taught’ history seeming to be a procession of great men, great battles, great events, that half the world’s population is invisible, and that this invisibility is somehow uniform throughout history. Sarah presents Renaissance women to us in her novels – in convents, as courtesans, at court – living unexpectedly rich and varied lives, even though they may be distanced from direct involvement in the ‘great events’. Lucrezia Borgia is almost invisible, except for the gossip put around by enemies of the Borgias. Pinturicchio’s depiction of St Catherine of Alexandria may be the closest we have to a portrait of her, but as a dynastic asset she was arguably as important as her father Rodrigo and her brother Cesare. Although she was only thirty-nine when she died of natural causes, she outlived them both. In the Name of the Family introduces to Sarah’s readers to a young Florentine diplomat – Niccolo Machiavelli. This is a name that often strikes a chill – after all, the adjective that derives from his name is used to describe the ruthless and amoral wielding of political power – but a recent book by Erica Benner, Be Like the Fox, reveals a staunch believer in republican liberty and a scrupulous recorder of the realpolitik of Renaissance Italy. Sarah’s portrayal of him is that of a relative youngster, who has a wife back home who seems quite fond of him, and who worries about whether his attire is smart enough for his surroundings, whether his doublet is straight, and so on. He is a man who has been chosen for his diplomatic job because he shows much promise, but the wily observer has yet to emerge. Writing The Prince is many years ahead.

In the Name of the Family introduces to Sarah’s readers to a young Florentine diplomat – Niccolo Machiavelli. This is a name that often strikes a chill – after all, the adjective that derives from his name is used to describe the ruthless and amoral wielding of political power – but a recent book by Erica Benner, Be Like the Fox, reveals a staunch believer in republican liberty and a scrupulous recorder of the realpolitik of Renaissance Italy. Sarah’s portrayal of him is that of a relative youngster, who has a wife back home who seems quite fond of him, and who worries about whether his attire is smart enough for his surroundings, whether his doublet is straight, and so on. He is a man who has been chosen for his diplomatic job because he shows much promise, but the wily observer has yet to emerge. Writing The Prince is many years ahead.